Learning effects lead to path dependency

First Posted: 2021.05.22, Last Revised: 2021.05.22, Author: Tom Brown

- Learning effects lead to path dependency

- Including learning in your model => many distinct local optima

- => Diverse choice of low-cost future energy systems

- Can't just look at one

Conclusions from Niclas Mattsson's pioneering work in 1990s:

Learning by modeling energy systems

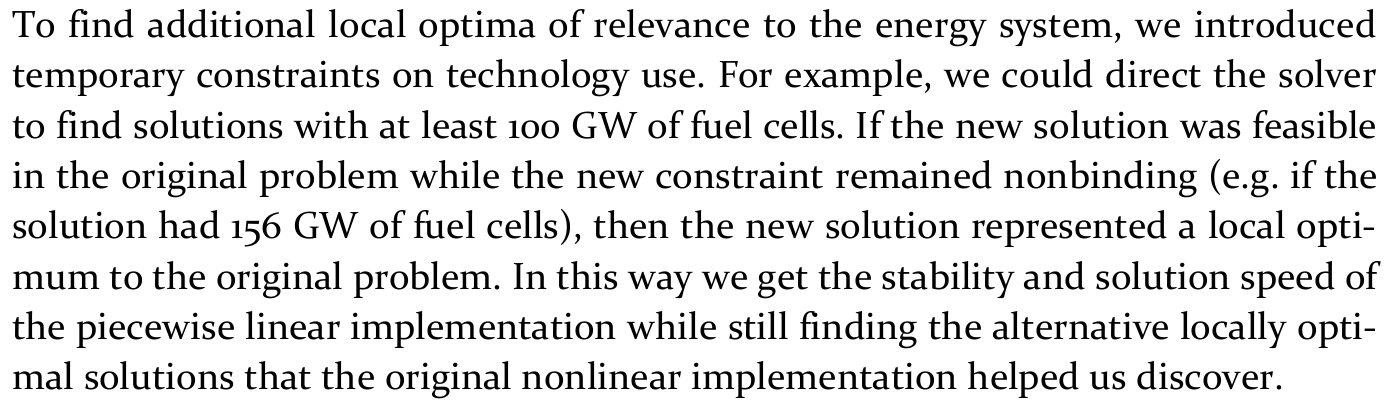

Figure 1: (Source: fabulous book Planetary Economics by Michael Grubb)

—

So what did Niclas do?

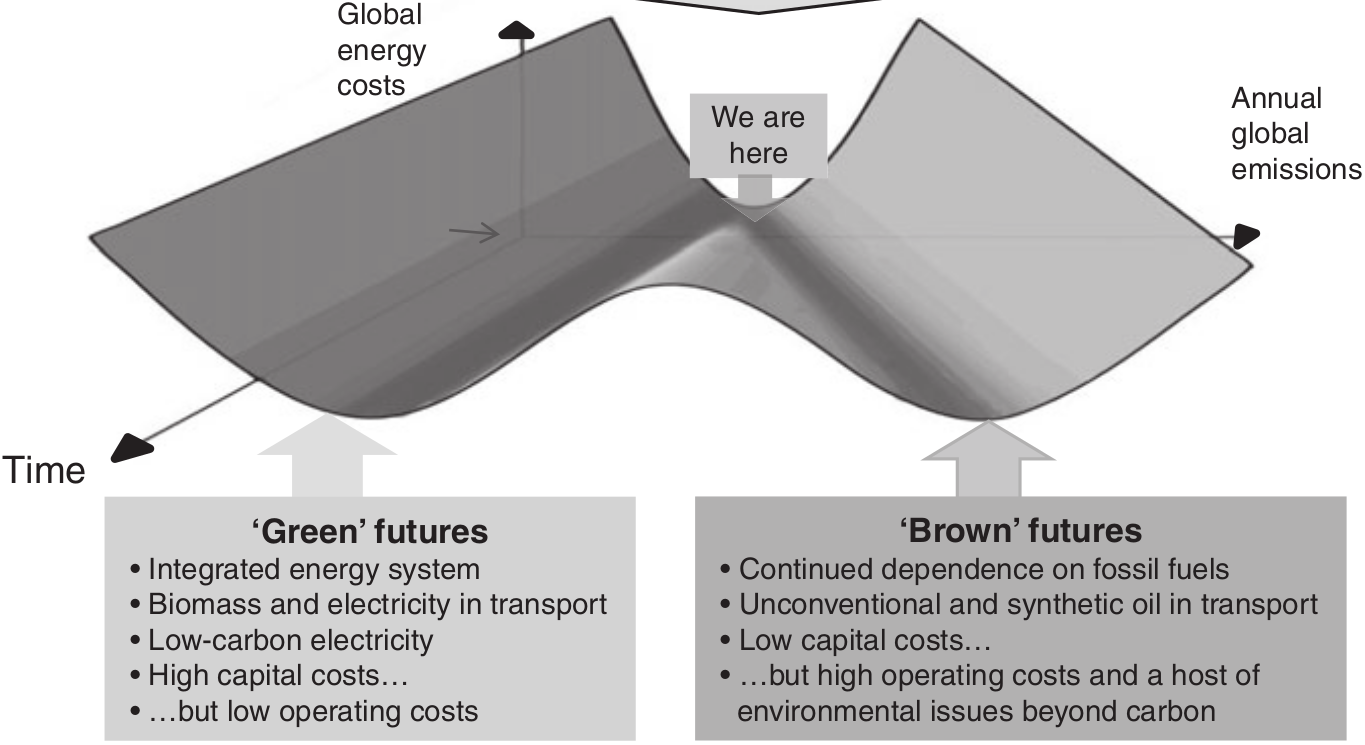

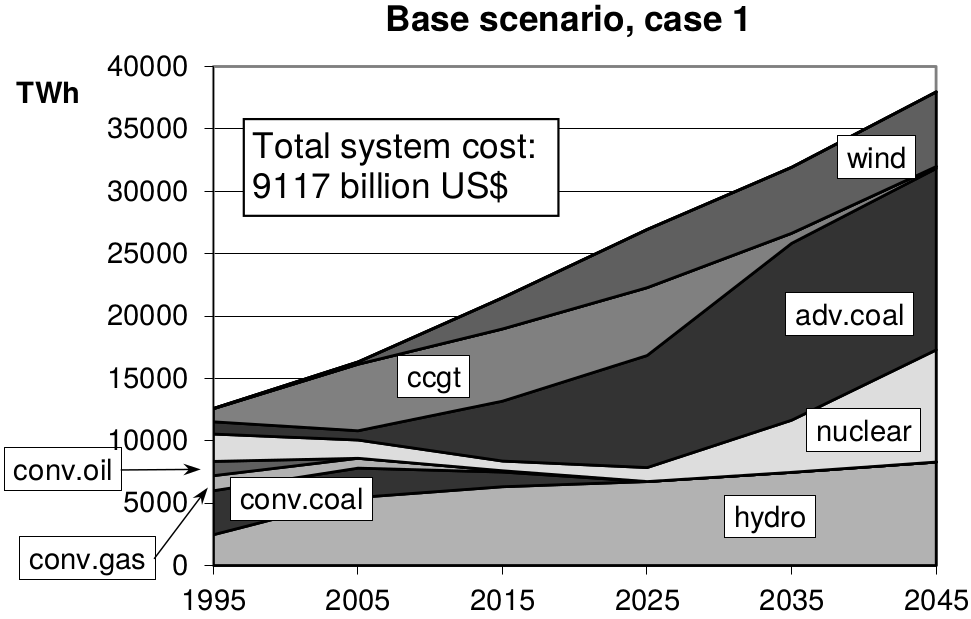

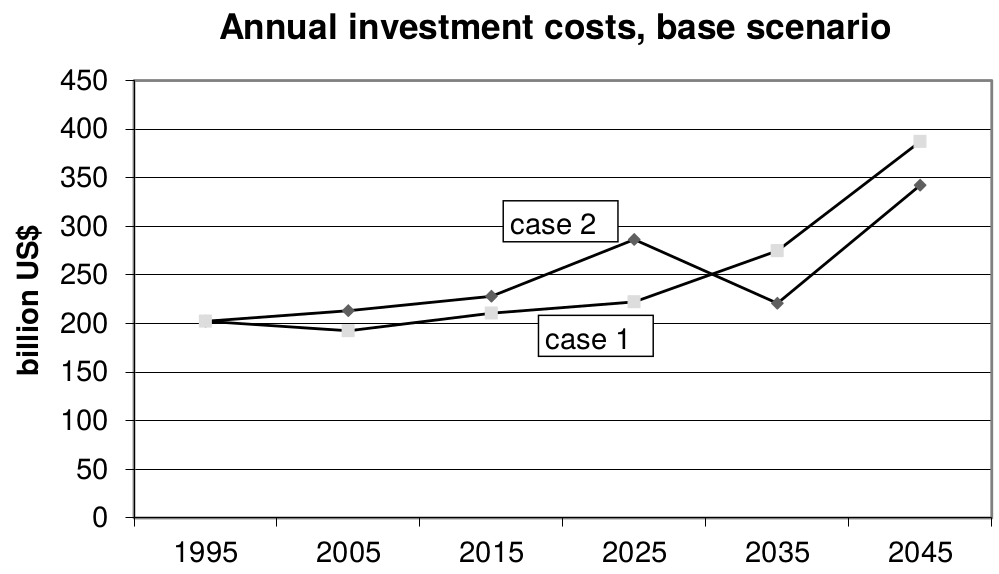

He ran an energy model with built-in learning curves and showed that with exactly the same model (same equations, all same data inputs, costs, etc.) you can get radically different energy pathways with similar total costs:

—

Case 1 is coal-heavy while Case 2 has lots of PV. They cost roughly the same.

Case 2 is different because large investments get triggered early for PV and other technologies, which take them down the learning curve, saving costs later in the simulation:

—

This phenomenon, that technology investments and learning now can save costs later, was well understood by the fathers of the German renewable subsidies programmes, Hermann Scheer and Hans-Josef Fell, which brought down the costs of PV.

—

How can the same model deliver such different results?

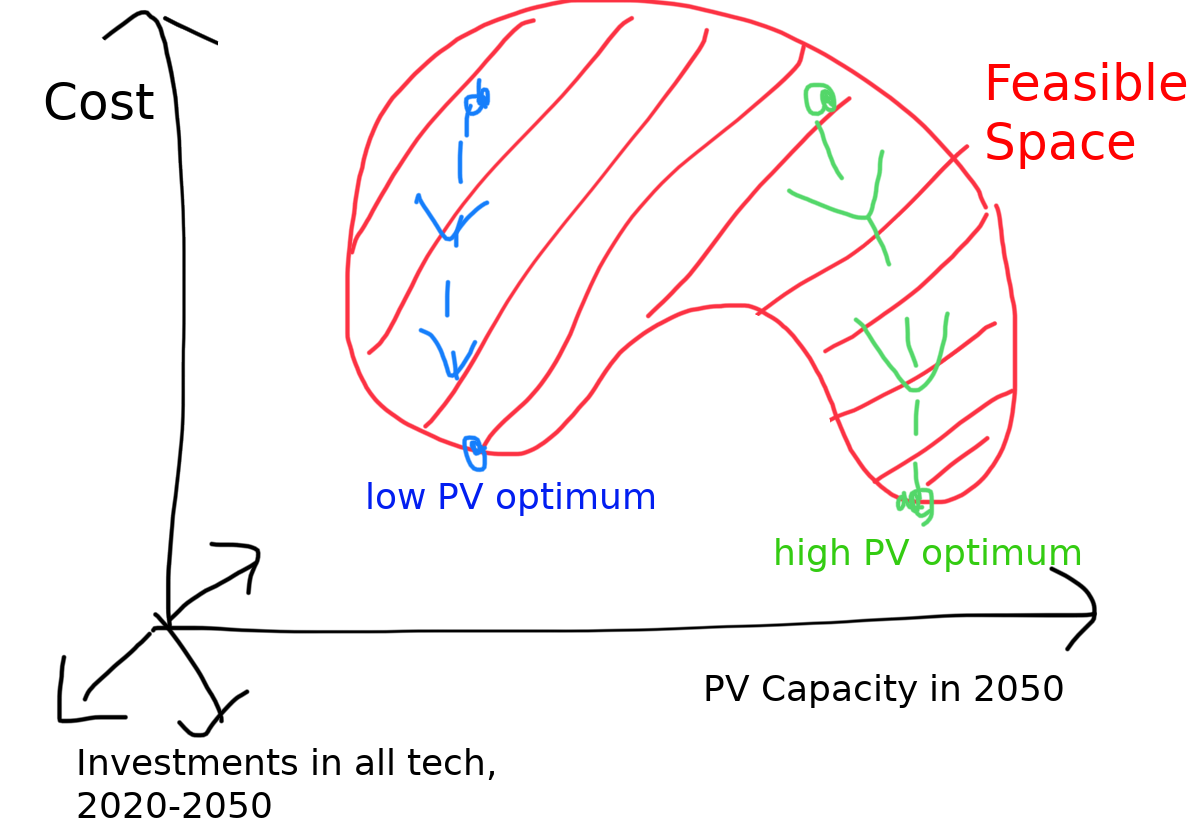

Because learning curves introduce non-convexities into the optimisation.

This leads to local optima in the solution space.

Depending on where the solver starts looking (green/blue), you end up in different optima:

—

If the solver starts its search on the left and looks for decreasing cost, it lands at the blue low-PV, high-coal optimum.

If it starts on the right, it lands in the green high-PV optimum.

It's hard to build solvers to find these different solutions, so they're often ignored.

—

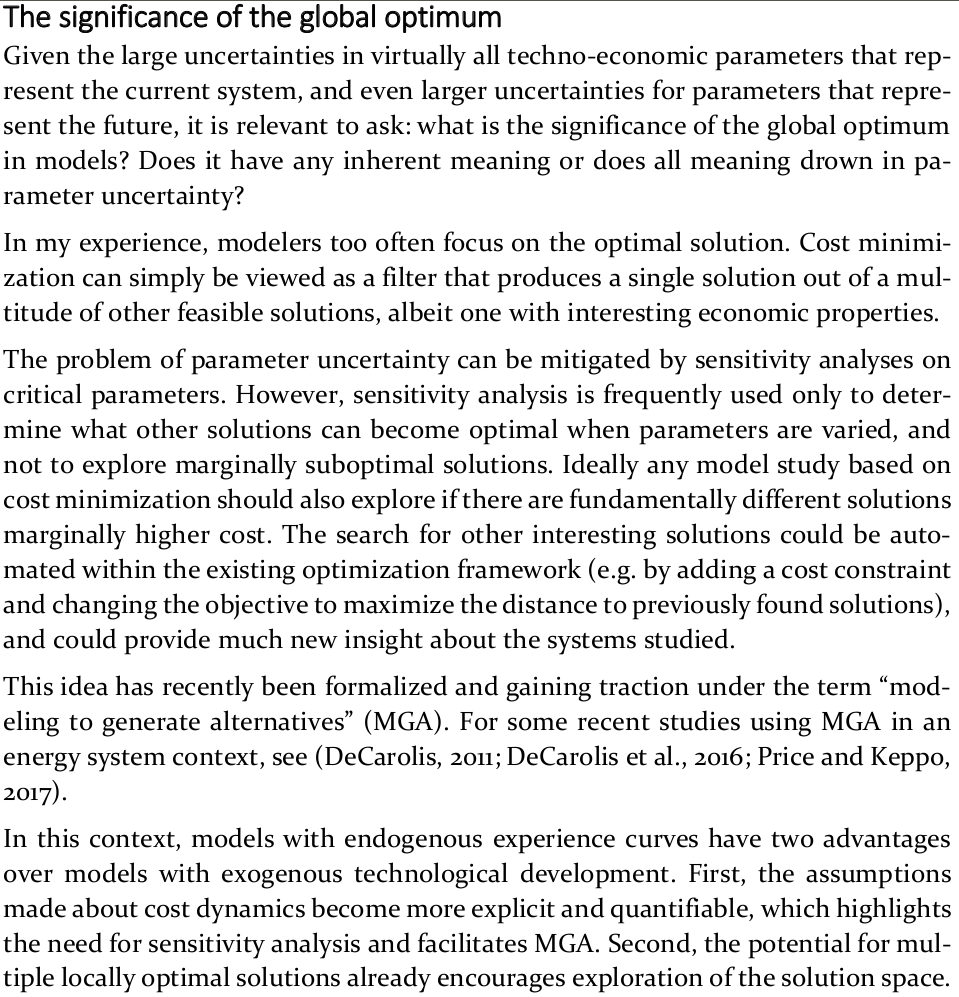

This diversity often goes unacknowledged in the energy modelling world where models that have endogenous learning curves aren't used to explore all solutions. (Please correct me if I'm wrong.)

—

Policy-wise, this general phenomenon of path dependency shows how we can choose (within limits) how we steer our technology investment towards solutions that society wants (e.g. high acceptance, high co-benefits, etc.).

—

Conclusion: there are lots of different possible low-cost low-emission energy systems out there, depending on which technologies we choose to invest in.

—

Now for some more technical details.

This is NOT the same as the near-optimal solutions that crop up in the Method to Generate Alternatives, since those solutions are convexly connected to the global optimum. Here we're talking about far-away distinct near-optimal solutions.

—

Niclas has some comments on this:

—

What about models that approximate the non-linear learning curves with a piecewise linearisation to turn it into a MILP? (A technique Niclas co-invented with Sabine Messner)

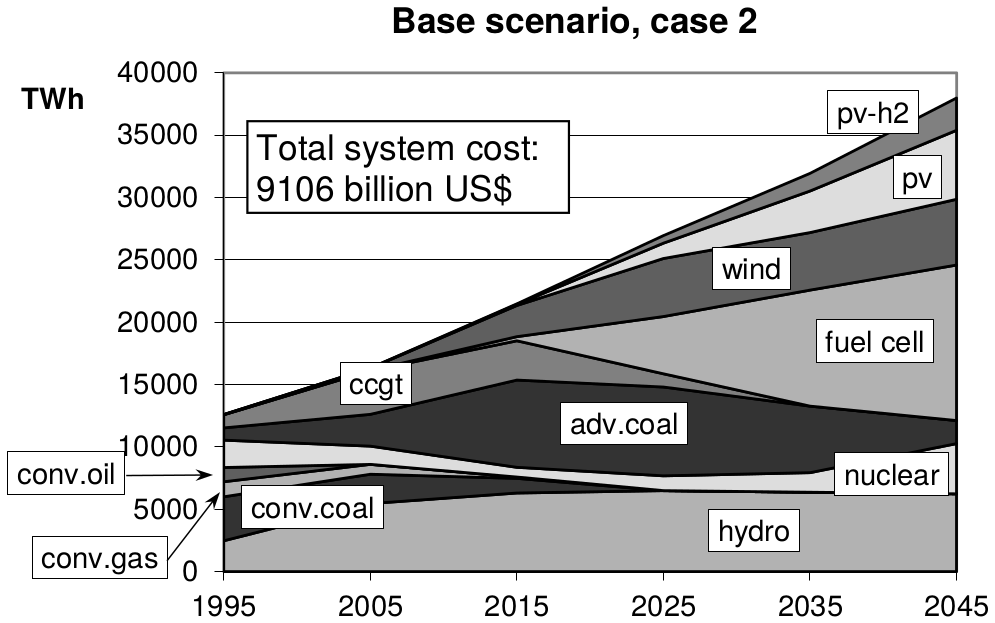

Niclas has a trick to find the local optima by forcing constraints and seeing if they become non-binding: